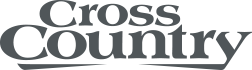

Anthony Moore investigates sea thermals and going XC from the beach. Think again about what you think you know – because anything is possible…

Flying XC can be wonderful, but with ever-increasing distances being flown it can also be frustratingly limited. In northern Europe and the UK in particular there is a lot of airspace – and then there is the coast.

Look at tracklogs online and you will see that, outside of the mountains, a significant number weave and wiggle their way through the convoluted 3D maze of airspace only to be stopped by the ultimate barrier: the sea.

The coast has long been an important feature of flying in a positive way. When flying from inland to the coast, seabreeze fronts can be used to advantage by the skilful pilot to add many ‘easy’ miles to a flight. And reaching, and being stopped by, the coast may be annoying but it’s also a great target, which usually means you maximised the day.

Coastal soaring can be a luxurious, decadent, mellow and chilled counterpoint to the sometimes hectic demands of inland thermal flying. The scenery can be stunning, and sometimes the location can be remarkably remote and inaccessible by other means. Often whilst coastal flying the pressure to fly distance is removed, leaving just the pure beauty and unlikeliness of the sport to enjoy in an unfettered way.

Sea thermal

Imagine a tracklog that shows a fairly small but typical flight, ending at the coast. Look again and turn it around. The launch is coastal, the flight runs from west to east. In recent years a growing number of flights have used the coast as a launch pad. I am not talking here of coastal soaring (beautiful as those may be) but of ‘proper’ XC flights.

To the uninitiated this may sound unlikely. Isn’t coastal air damp, soggy, heavy and unsuitable for thermal flying? I used to believe this but it is demonstrably not always true. Sea thermals undoubtedly exist – how else could we fly to 650m a kilometre out to sea in front of cliffs less than 30m high?

These sea thermals can be used to gain enough height on the coast to make the difficult transition to inland thermal flying, thus providing many non-traditional potential XC launch sites. Better yet, many of these are miles from crowded inland sites and from crowded airspace, opening up new long-distance potential, and new adventures.

Recipe for success

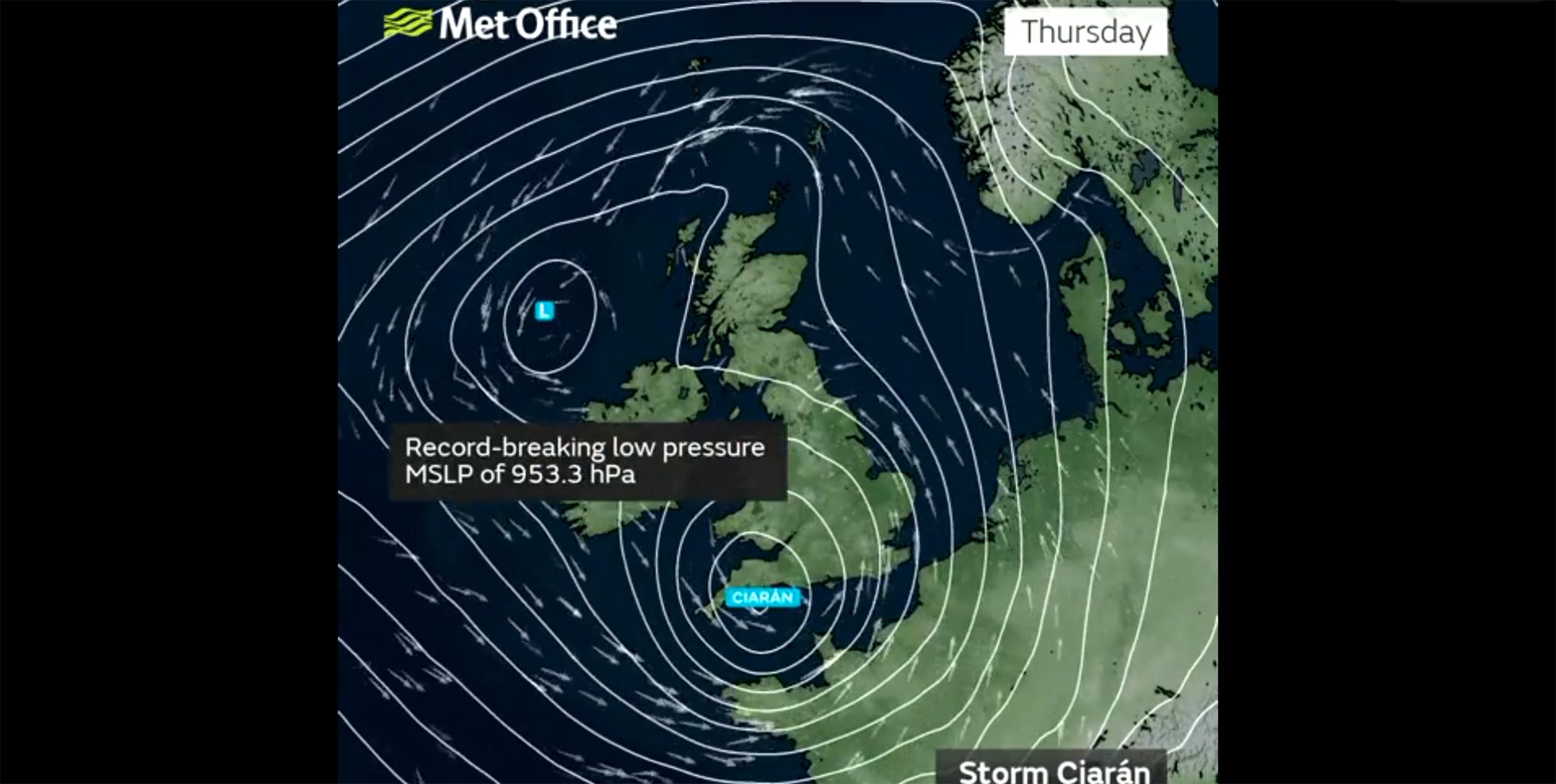

So how does it all happen? What is the recipe for success? Take a sea warmed by a long hot summer, look for a cold or cool autumnal or even winter’s day, preferably with a relatively dry air mass, add a light (or even fairly strong) onshore breeze, along with a pinch of adventurous spirit, get to the right launch at the right time and off you go!

It seems to work. The theory of course is that the warm sea heats the air above it, which then acts as a source of relatively hot air blown towards the fantastic trigger of a long cold coast. No doubt meteorologists would make much more of this, but this seems to be the essence of it.

When?

Experience suggests that autumn is the best season – the sea is nicely warmed, days suddenly get cooler. Remember that the seasonal sea temperatures lag several months behind the air temperatures, so cold winter days can also be good, expanding the season considerably. Having said that, numerous big flights have been made during the summer months, so it is clearly not just an autumn/winter phenomenon.

Like what you’re reading? You will find plenty more like this inside Cross Country magazine. Here’s what some of our readers say:

“Honza Rejmanek’s new met article helped me enjoy a magical flight yesterday. Thank you for a wonderful publication” – Dan Corley, USA

“I love your magazine more than anything.” – Urs Haari, Switzerland

“Cross Country has a massive impact on pilots’ awareness, worldwide. Great job in inspiring and sharing knowledge!'” – Ben Kellett, New Zealand

Where I live in the UK, RASP (a nationwide soaring forecast) charts seem to be reasonably accurate at predicting how close to the coast normal thermic activity will start – and of course, the closer and stronger the better. Early morning and late evenings are often good for the sea thermals, presumably because the temperature differential is greatest. This of course leads to another advantage for those looking for distance – the potential early start gives plenty of time in the day.

Where?

So far most of the successes I know of have been from north or north-west facing coasts in the UK – presumably because they face the oncoming cold air masses. It seems likely that the east coast should work in much the same way too. I suspect that southern coasts have a lower chance as generally onshore breezes (in the northern hemisphere) herald warm weather inland and so don’t create the required temperature differential. Presumably the same principles apply to other coastal areas

SEA BREEZE FRONT: Approaching the coast on a summer’s day in England. The skilled pilot can use the sea breeze front to make more distance parellel with the coast. Photo: Carlo Borsattino / Flybubble.com

How?

At its most basic, it’s a question of launching, soaring along a suitable coast, climbing and then blasting off inland and flying just the same as you would from your ‘normal’ XC site. Of course as ever there is a bit more to it than that.

Generally, sea thermals are relatively gentle, but often fairly large, so gaining height initially is a bit like restitution flying, gentle lazy circles seem to work better than tight coring. Climbs are typically in the order of 0.5 to 1.5m/s but can occasionally be up to 4m/s.

If winds are strong and climbs weak, then you will need to elongate your upwind leg to stay in position in front of or over the coast. Clouds can be spotted a long way off and you can estimate their trajectory and use the coast as a racetrack to intercept likely looking cumuli.

With faith you can be a surprisingly long way out to sea slowly climbing. Tex Beck, an experienced coastal paraglider pilot from Rainbow Beach in Australia talks of, ”Finding a line of lift that is long, narrow and inline with the sea breeze. On one day at Rainbow Beach I found three of them in a row, but at the end of each I turned 45 degrees each time to find another one and found myself around 4km to 5km out to sea at about 1,000m.”

Regular coastal pilots will sometimes see evidence in the shape of flocks of seagulls all gliding in a straight line perpendicular to the coast that support a hypothesis of convergence. (It goes without saying of course that you must always be within comfortable downwind glide of a potential dry landing place. Sea landings or a reserve ride are not good options!)

CONVERGENCE: Climbing out in convergence on the coast in the northwest of Scotland. Photo: Jérôme Maupoint

Going inland, the tricky bit comes when you go for the transition from coastal mode to inland mode. There is usually around 2km to 10km, sometimes more, where the lift is weak and hard to centre before linking into conventional inland XC flying. It is here that the day is won or lost: clinging on to every scrap of lift or zeroes counts. Subtle handling and good thermal centring skills and patience are needed; each kilometre further inland increases your chances.

Typically, cloudbase is low and climbs are slow close to the coast. Every turn and drift in the breeze gets you into better conditions. You can of course load the dice in your favour by getting as high as possible on the coast, studying the clouds downwind and judging your moment. Earlier in the day gives more time for a long XC, but also makes the transition trickier as inland thermals haven’t reached their peak. Once you have crossed this ‘transition zone’ you are back in conventional XC mode.

Conditions that seem to work best are predictably light enough to soar so you can wait for that thermal to develop and generate and work out where the triggers for the day are lurking. Be ready to latch onto it when it does break.

Additional Barriers

So what are the barriers? Obviously they may be physical, as in the meteo conditions to make it possible. They may be to do with airspace or unlandable terrain downwind. They may be psychological, as in, “well nobody does that”. Possibly this is the biggest barrier – next time you are coastal soaring think about it and maybe give it a go. Maybe we just have to dare: it might open up a whole new range of opportunities.

For me and a band of local pilots in North Devon in southwest England this approach has opened up some wonderful days of flying right on our doorstep, some of it most unlikely. Eighty kilometre flights from a take-off 10m above the high-tide level anyone?

Of course, in the circular nature of things new limitations arise: Joey Jordan and Richard Osbourne (see interview) have already reached the opposite coast in north-westerlies. In doing so they opened many people’s eyes to what is possible from small sites on the coast. Boring soaring, it isn’t.

THE NORTH DEVON COAST: Richard looks for sites that allow you to soar in strong wind, with large flat beaches that heat up in the sun. Photo: Anthony Moore

Like what you’re reading? You will find plenty more like this inside Cross Country magazine. Here’s what some of our readers say:

“Honza Rejmanek’s new met article helped me enjoy a magical flight yesterday. Thank you for a wonderful publication” – Dan Corley, USA

“I love your magazine more than anything.” – Urs Haari, Switzerland

“Cross Country has a massive impact on pilots’ awareness, worldwide. Great job in inspiring and sharing knowledge!'” – Ben Kellett, New Zealand

Coast to coast with Richard Osbourne

Richard Osbourne regularly flies XC from a coastal site in North Devon, England. He’s spent years studying how to get away from the coast and recently flew a personal best of 161km from it. Club mate Anthony Moore asks him how he does it…

What makes your site so special?

Woolacombe faces predominantly west. The beach in front is huge and surrounded by high ground, creating a massive bowl effect. A key factor is it is flat – and due to our huge tidal range, a massive area is exposed to the sun when the tide is out.

Behind the beach are dunes covering almost as much area as the beach, but they present a better angle to the sun. The dunes form rising ground with steep gullies which trigger thermals and channel warm air from the beach directly onto the hill. The dunes and hillside behind are regularly cleared, leaving dark brown patches creating perfect thermal makers.

So is the scene set for XC?

Not quite! We all know that cold damp sea air suppresses thermal development as it flushes over the land, so despite all the above, the odds are still stacked against us. What is needed now is the perfect topography behind the hill. Land that drops away, forcing warm air to relinquish its hold on the ground. Topography that can make more thermals. Fortunately we have all that, along with a quarry and a golf course thrown in for good measure.

Significant too, is that much better thermals are constantly leaving from the bustling holiday villages at both ends of the beach. The cloud streets from these ends are often reachable if you are high enough behind the hill. Finally, there is one last hurdle to pass in the form of a line of wind turbines. When they were put up we thought our game was up, but amazingly the opposite proved to be true. It turns out they trigger thermals. Many times now I have had enough height to safely search along the line of turbines and directly above them, and found good climbs. Now I regularly use them. All that remains is to go XC.

So is it all easy?

Hmmm! I tried and tried, peppering the landscape behind with landing places. My efforts revealed two main reasons for decking it. One, flying out of the first thermal, which is much easier to do than normal. And two, not linking in with a normal inland thermal at the crossover point when the first weak, low base, short-lasting one gave out.

I went back to basics and studied the local maestros, seagulls. I found a place where I could watch the gulls from side-on as they left the hill. Bingo! They revealed their secret. What I saw was that they flew long, flat, ovalised 360s as they tracked back with the thermal. When they faced into wind, they turned quickly, but critically, only when they had found the upwind edge of the thermal and not a second later.

Next they drifted back to the downwind edge, travelling what looked too far, before facing up again and repeating the process. That’s when the penny dropped as to the shape of the thermal as it tracked back. Because of the fresh breeze, the weak thermal was laid over at a shallow angle and that’s why I was flying out of the upwind edge so frustratingly. I realised too, that once you lose this thermal, you’re likely to descend at the same sort of angle as the thermal, thus explaining why I rarely found them again.

I couldn’t wait to try again, but though I got immediate results, I still lost the lift far too easily. I worked out that our wings are slow to respond to input, and this fact was causing me to whizz past the edges of the thermal. The solution was to learn to anticipate where the edges were and turn within them. I was getting it now. I could reliably stay in the lift, but still something else was needed. The lift is so delicate that often just the physical action of turning was enough to critically unsettle the wing. So I practised turning the wing even flatter, even slower and with massive amounts of weightshift to increase efficiency.

The results were stunning. I found myself regularly keeping up with the gulls (a dream come true) which meant I could use them as markers. In essence, I had now found a way of drifting back far enough through poor air to link in with normal inland thermals, but with the added advantage of doing it in what might be top-end wind speed on an inland site.

So do you think this is specific only to your coastal site at Woolacombe?

No! Once I had nailed the technique my performance started to improve and over the years I have completed many flights from various sites on the coast. My first coast-to-coast was Woolacombe to Lyme Regis, 102km. I looked at different sites to see if it could be done elsewhere and found that it could.

Tell me about your latest coast-to-coast

I had planned it two days before the flight, having seen conditions shaping up nicely and also because I made a declaration at 161km. Woolacombe to Corfe Castle in Dorset is my personal best from the coast. I had wanted to make the town of Swanage 10km further on and right on the coast, but an air show that day meant I had to land at Corfe. On the day I had plenty of height to get to Swanage, despite having to punch a sea breeze headwind.

What conditions do you look for?

I look for the first, preferably second day post cold front, giving backing northerly air, having tracked down from polar regions. Just enough of a lid of high pressure to prevent runaway instability, a fresh breeze, around 15-25km/h; high cloudbase to cope with the stronger wind downwind and to get as high as possible at take-off, though this is never higher than 700m ASL near the coast. Any additional suppression of thermal production, such as top cover, is no good at all. I use sea thermals in the autumn, but of course the days are shorter then, so more and more I have practised getting away at peak times in the conventional summer flying season. Sea thermals, though, undoubtedly make the whole process of getting away much easier

FLAT TURN: The transition from soaring to XC is ‘delicate and requires thermalling flatter, with massive amount of weightshift to increase efficiency’. Photo: Anthony Moore

What happens when you get near the opposite coast?

If I make it, I look for sea breezes coming directly at me. This can have two benefits. The flight can be extended by flying along the convergence cloud or coastal ridges, and two, landing can be much easier in smoother more laminar air.

What I set out to do, was understand the nuts and bolts of it so I could plan flights more predictably in an endeavour to extend the boundaries still further.

Any thoughts for the future?

How about harnessing seabreeze convergence fronts to form one or more legs of a triangle? If it’s already been done I’d love to hear about it!