How do you find the core of a thermal? Bob Drury explains

ONCE YOU HAVE found a thermal, the next thing to consider is what to do with it. It’s a big subject to try and explain in an article, similar to trying to explain to a toddler how to walk; no matter how good my diagrams and words, you really can’t substitute experience. Lots of flying and lots practice is the only answer.

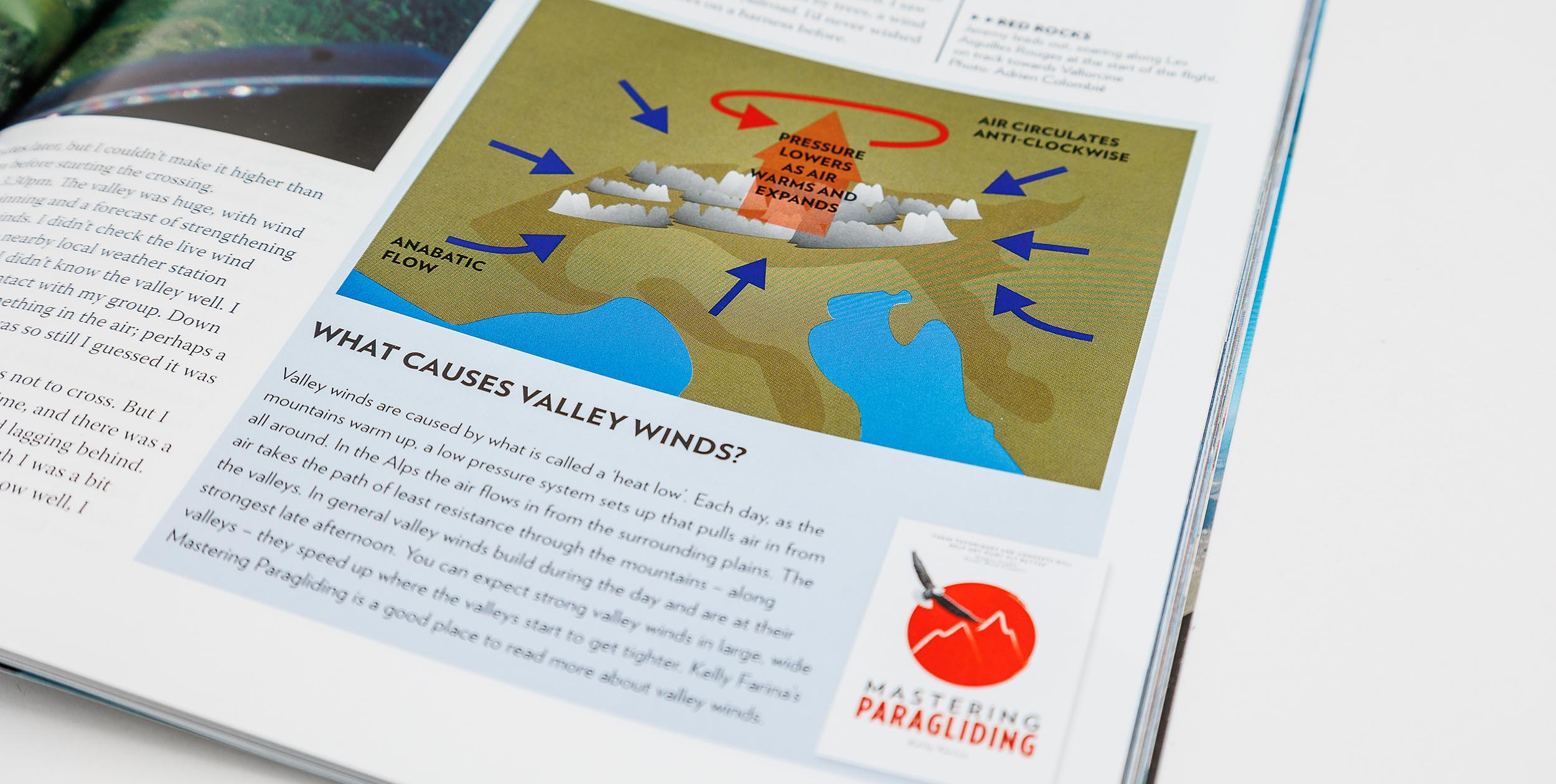

Like so many aspects of our sport, our human perception of what we should be doing vastly over-complicates the subject of thermalling. All the technology at hand means nothing if you can’t find the strongest part of the thermal. Almost without exception, all thermals get drifted in either a valley wind or by the true meteo wind, and some might even change direction with altitude as they pass between the two.

Keeping track of which way the thermal is drifting will do two fantastic things to your flying: firstly it will help you stay in the thermal, and secondly it will help find the strongest part of lift within the thermal.

Fly 360s, not figure-eights

When you hit a thermal you should try to establish a 360 pattern as soon as possible. Turning in circles is by far the best way of tracking a thermal, and equally it is also the most efficient way of keeping a glider in a specific piece of air. If you fly a figure-of-eight pattern, you are basically doing gentle wingovers, which are effectively just another good way of losing height.

In comparison, if you can establish the glider in a 360 pattern, usually just the very first 360 turn is inefficient, provided you don’t allow it to drop into a spiral dive. Once the glider has established an angle of bank, the glider will stop trying to dive to regain level flight.

‘Four elephants’

The first thing you should do when you hit lift that you suspect is a thermal, is to fly out to find deep into it to establish if it is big enough to turn 360s in. To do this, some pilots employ the ’four elephants rule’. Once you hit a thermal you simply fly straight on into it, counting “one elephant, two elephants, three elephants, four!”

If you’re still inside the thermal by the time the fourth elephant comes along, then it’s big enough. Start circling. For myself, I just look back at the hillside until I think I am far enough away to throw in a 360 without hitting the hill.

That first turn is usually the worst as you haven’t established an angle of bank yet, but once you’ve gone around once, the glider will settle down.

Which direction you circle in is much less important than many think unless you are low. If you’re sharing your climb with others then you must circle in the same direction as them.

If you are close to the terrain and there’s a crosswind then circle in the direction that makes the upwind side of your circle the one closest to the hill. That way you’ll be travelling the slowest when you’re the closest to the ground. Competition organisers set compulsory turn directions for this exact reason.

If you are low then you should fly tight and aggressively, as you are more concerned with hanging on to the thermal than anything else. If you feel a substantial difference in the thermal’s strength towards either direction, then turn towards it. However, if you’re free of other aircraft, clear of the terrain and not worried about going down then you should simply turn towards the side that feels most comfortable.

Searching for the core

Once you’ve managed to complete three 360’s in a row in constant lift, with the vario beeping all the way around, then you can generally consider the thermal caught and you should start looking for the strongest lift.

To do this, fly towards the upwind side of the thermal by straightening up slightly each time your 360 pattern faces you into the wind.

Once you reach the upwind edge of the thermal, you’ll often feel an increase in lift as you encounter the dynamic assistance of the air blowing up the side of the thermal. But then, if you fly too far, you’ll fall out into the sink.

However, falling out of the upwind side of the thermal is never as bad as falling out of the downwind side. If you do then quickly turn the glider around, and fly back downwind, through the dynamic assistance to the strongest lift.

Falling out of the back of the thermal is much worse. You’ll fall into heavy sink and then have to turn back into wind to fly back slowly, through the sink, into the weakest lift.

Look upwind for the core

There are two reasons why the strongest lift lies at the upwind side of the thermal: firstly, the stronger the lift, the more vertical velocity it has, and the less it is affected by the horizontal wind.

Weak lift is blown to the back of the thermal, leaving the stronger lift at the upwind side. This is why you always see good pilots searching for climbs a long way out front of the hill on windy days.

Secondly, because the thermal has a mass of its own, some of the horizontal wind will actually ride up the front face of it, rather as if it were a hillside, creating lift. It’s for this very reason that gliders can soar up the sides of cumulus clouds, and why pileus caps appear on the tops of cumulus when the wind blows over them.

As you search around in the thermal for the strongest lift, you might feel a strong pull on one side of the glider. If it’s on the inside of the circle you can simply tighten up even further to centre the core, but if it’s on your outside wing, it also often pays to tighten up and quickly bring yourself around 270 degrees so that you can straighten up and fly back to where you felt the stronger lift.

Avoid changing direction

Personally, I rarely, if ever, change direction in a thermal unless it’s really big. Changing direction in thermals scrambles most pilots’ mental mapping, and it’s also inefficient as discussed earlier when we talked about flying in figure-of-eight patterns.

As the thermal drifts, it’s imperative that you constantly assess which direction is into wind. You can do this by feeling which direction you face when you fly slowest. Remember that this may not be exactly 90 degrees from the slope, as the thermal may be drifting across or even away from it, especially if you are flying in mountains.

When you’re close in to the terrain it’s easy to keep track of this, but as you climb higher it becomes harder to judge. GPS systems that give you your ground speed can help, but it’s more important that you constantly update your picture by staying alert and thinking.

Finally, thermalling is not a science, it’s an art. It’s difficult to describe in words alone, yet I know of several so-called ’rules of thermalling’.

The first is: Turn tighter in strong lift and flatter in weak lift. The first part of this rule aims to keep us in the strongest lift for as long as possible: by turning tightly hopefully we won’t lose the core. This is a technique to help you hold onto a core once you’ve found it.

But, the second part of this rule tells us to widen our circles within the thermal to cover more ground, and increases the chances of bumping into a core. This rule is the rule of choice if we’re either in a strong climb or hunting around within a thermal looking for one.

However, there is a second rule of thermalling that appears to contradict the first. It says: Turn as wide and flat in strong lift as you can and turn as tight as you can if you fall out of it. This second rule appears to contradict the first until we look closer.

By turning as flat and wide as possible we maximise the performance and climb rate of our glider, because ultimately a glider climbs best in a straight line, without any angle of bank. But if we lose the core and fall into weaker lift, we should turn quickly to get back into it – even at the momentary expense of our sink rate. In reality it’s far more important to be climbing in the core, than to suffer a lower sink rate for a few seconds.

Even when you’re established in a thermal, it’s important to keep monitoring where the strongest lift is, by listening to your vario and constantly updating your picture of the thermal. If you ever make two 360’s the same, you’ve let yourself down, because you’ll have taken in no new information.

If you do fly through an area of stronger lift, remember where it was, and on the next time round, flatten out your turn to take you deeper into the area of stronger lift. Fly straight ahead until you pass through the core, then turn tightly again to try and re-centre yourself back in the core. This will help you stay in the strongest lift for as long as possible.

Good pilots always want more from the lift so they explore within the thermal. The really good guys in competitions often don’t turn very tightly. Instead, they appear to wander about the gaggle picking off the best bits of lift. That’s because they stay alert to all the information that the rest of the gliders are giving them. If someone rises slightly faster than them, they fly straight over to them and profit from the other pilot’s core.

Remember it’s not how you fly your glider that counts! It’s where you fly it!

For more quality tuitional articles like this one subscribe to Cross Country magazine. Click here to subscribe.